The EFL Trophy, has there ever been a more divisive competition? Never particularly popular, it descended into farce this year with the introduction of Under 23 teams from the Premier League. A boycott by lower league fans sent a strong statement of intent, but we now face our fourth trip to Wembley and, perhaps, the best opportunity for silverware in over 30 years.

There has been lots of very worthy commentary why people are not going to Wembley. It is very easy to believe that boycotting is the only moral option.

I decided a couple of rounds ago that I would probably go to Wembley despite being a supporter of the protests around the country. In essence, I’m following my heart, which wants to go and not my head which tells me to stick to my principles. However, the more I think about it, the more I’m comfortable with the idea. Here’s why…

Boycotting Wembley won’t work

The boycott certainly had a strong symbolic impact; but it was never a popular tournament in the first place so it wasn’t difficult to empty the stadiums. A bit like organising a boycott of Brussel sprouts; it would be full of people who would never eat them in the first place. Many thousands of people like me wouldn’t have gone to games in the early rounds anyway, so boycotting was hardly a chore. Those who would have attended early rounds but didn’t because of the boycott was relatively small. Comparable figures are difficult, but the crowd for Bradford this year was 2,247 compared to Yeovil last year which was 2,532. That’s a drop of just 12%. There was talk about the ‘1500’ who would have been at Luton if there’d been no boycott, but in reality there was only 40 fewer fans at Kenilworth Road than the last time we visited in the league. If 12% boycotted the final, we would take just under 30,000 fans; more than Barnsley took. Nobody is going to notice a 12% drop in a Wembley attendance, particularly in a competition that has had final crowds as low as 21,000 and as high as 80,000. Nobody knows what a good EFL Trophy Final crowd is anyway. The early rounds boycott made a statement, and it was more powerful because it spread across the tournament and across many teams, a Wembley boycott would have to be unimaginably massive to have any impact at all.

The boycott made A statement, it didn’t make THE statement

When will we know the boycott worked? When b-teams are not playing in the Football League, I suppose. We know that they aren’t at the moment and they won’t be next season. We don’t know beyond that and sadly we’ll never know whether it will happen in the future. Let’s face it, Premier League clubs have enough money to buy their way into the Football League if they choose. If each contributed the equivalent of an average Premier League right-back, they would have more than enough to bribe their way to anything. If the Premier League want this to happen, then they’ll make it happen regardless of the moralising of a boycott. So, the boycott sent a signal – which the Football League will already be painfully aware of – but the boycott didn’t, and never will, solve the problem once and for all.

The experiment didn’t work

Fielding Under 23s didn’t work on practically every level. It was grotesquely unpopular, damaging the Premier League brand. Several Premier League teams didn’t even engage in the experiment anyway, which shows just how little interest there is in the idea in the first place. Those who did materially failed to comply with the spirit of the idea. Several clubs fielded over-aged players from overseas, a clear snub of the idea of giving young English talent the opportunity to test themselves. Furthermore, those who did enter did really badly. The last Premier League team standing, Swansea, made it to the quarter-finals, a third went out in the group stage, 75% were gone by round two. Apparently Joe Royle said that Premier League youngsters had gained experience of ‘direct balls from Cheltenham’, which isn’t the best preparation for facing Barcelona in five years time. If there was an appetite for this idea, there’s not much to suggest it should be pursued.

There’s more than one way to protest.

Why is there a protest in the first place? Because we believe that lower league teams have a right to compete and thrive. And what proves that? The thousands of people who attend games away from the glare of the Premier League. And what is the best way to keep proving that? To keep going to games. Say the final only attracted 10,000 people, does that prove the boycott worked or that the lower leagues don’t have the grassroots support it claims? What has more impact; nobody attending a game which people claim nobody cares about anyway or a capacity crowd that emphatically proves the vibrancy and relevance of the lower leagues? When the FA bid for the 2018 World Cup they made a point of highlighting the vitality of the English game using our Conference game against Luton as an example. There would be no stronger statement about the importance of the lower leagues than if the stadium was full.

The kids

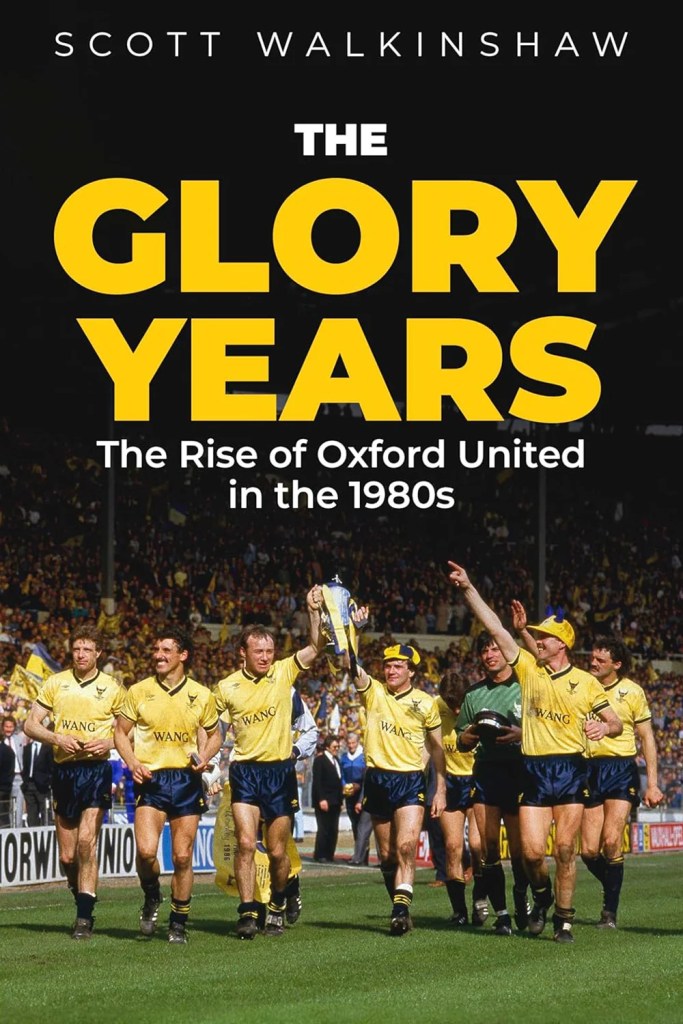

I started going regularly to Oxford at the dawn of the Glory Years. In three years I saw two promotions and a Wembley appearance. The experience forged something very deep in me. Had I not been through that, it’s quite possible that me and people like me would have had no more than a passing interest in the club. The last 18 months have been the best Oxford have had in the intervening 30 years. Kids living through this period are collecting memories which will get them through any future and fallow years. Failing to use these experiences risks them drifting towards the bright lights of the Premier League where they have glory on tap (I would probably have been an Arsenal fan, for example). The kids don’t understand nuanced arguments about Premier League academy teams, they want to see teams picking up silverware at Wembley. If that is Oxford, they’ll stick with us for life.

John Lundstram

Last year John Lundstram missed out on Wembley. Lundstram is one of a raft of players who has been persuaded by Michael Appleton that there is more to life than hanging around in Premier League loungewear hoping that you might get a substitute’s appearance in the early rounds of the League Cup. Firstly, I want him to love playing for Oxford and him winning in front of 30,000-plus yellows will ensure that is the case. Secondly, the more young pros who see what is possible in an Oxford shirt, the more likely they are to sign, the more glorious that looks the more attractive we become. That makes us more sustainable and relevant.

Joe Skarz also missed out last year; these are players that we want to celebrate, we want them to win games in an Oxford shirt at Wembley in front of Oxford fans. This is a chance; why would you dampen it?

I’m 44

I have spent most of my life not seeing Oxford United get anywhere near Wembley. It’s conceivable that I’ll never get another chance. If I don’t take chances when they are presented to me, I’m frankly a bloody idiot.

None of this detracts from the effectiveness of the boycott. In August and September, it made a clear statement about the strength of feeling on the issue. But, those who are resolutely planning to stick to their principles for the sake of, well, sticking to their principles might find that they are turning from principled freedom fighters into ineffective ideological bores. Protest and disruption is certainly part of any activism, but offering some sort of demonstration of strength, a positive energy is similarly important. Going to Wembley is not necessarily an act of deceit but a demonstration of power.

Leave a reply to David Woollacott Cancel reply