Oxford has always been an educational hive where the world’s great problems are analysed and solved. It should come as no surprise that once-upon-a-time Oxford United had its own resident sociologist on the board. The multi-talented Desmond Morris combined work and play to produce The Soccer Tribe, a forensic scientific exploration of football. Will Richards dug in to find out what Oxford United was like over 40 years ago.

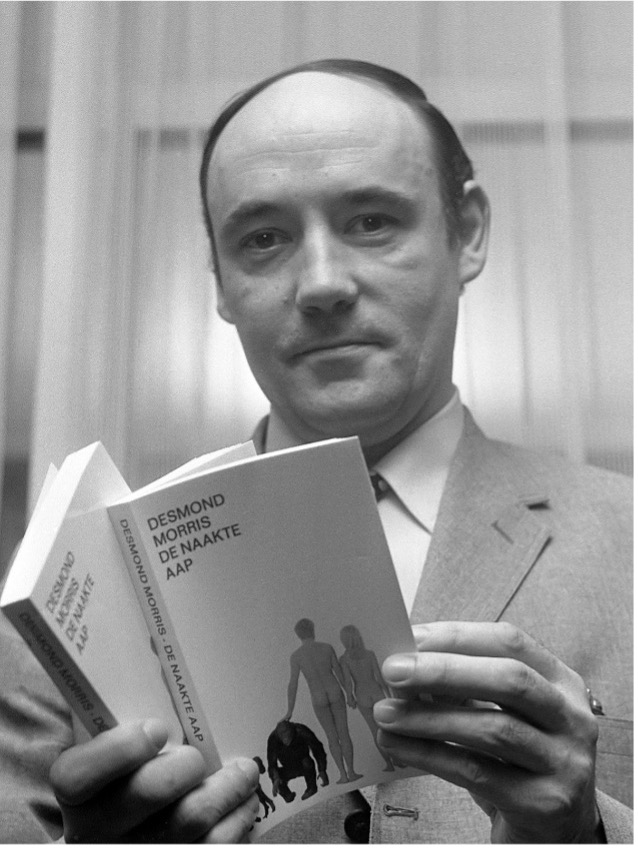

This is Desmond Morris. He’s what you might call a polymath. In his lifetime he’s written and presented hundreds of television programmes, has exhibited his paintings in several prestigious galleries and, as a noted researcher in animal behaviour, has written dozens of books including the best-seller The Naked Ape. He’s written extensively on the behaviour and sociobiology of humans and he’s clearly such an expert on human behaviour that he believed that combing over several strands would make people think he had a full head of hair. One of his best-known books is The Soccer Tribe, but more of that later.

Morris was born in 1928 in a village in Wiltshire, but let’s not hold that against him – he was very young at the time. His family moved to Swindon when he was five and he finally escaped at the age of 23, when he moved to Oxford to begin a doctorate in Animal Behaviour at the University Department of Zoology. In 1956 he moved to London and subsequently created hundreds of hours of TV for Granada, hosting the popular weekly show Zoo Time. In 1967 he published probably his best-known book: The Naked Ape: A Zoologist’s Study of the Human Animal, later translated into 23 languages. He returned to Oxford in 1973 to take up a position as a research fellow at Wolfson College, and in 1977 he was elected to the Board of directors at Oxford United Football Club.

Raging Bull

His most famous Oxford United-related claim to fame is that he redesigned our club badge, replacing the whirly ox head with a simplified design, said to represent the Minoan bull of Cretan legend. The new design first graced an Oxford shirt in a competitive match on 11/08/79 at home to Reading, before losing its TV Batman-esque circle and background the following season. To me the design closely resembles the Chicago Bulls basketball team logo which they have sported since 1966. Football magazine FourFourTwo have ranked club crests from best to worst and ours came in 51st (Forest came 1st, which is fine; Swindon came 31st, which is not fine) with their main take being that if you flip it upside-down, it looks like either an angry crab or an owl on a croissant.

The Insider

The Soccer Tribe was originally published in 1981, with a revised edition released in 2019. At 320 pages long, it’s a remarkably in-depth look at the whole phenomenon of the beautiful game, seen through a behavioural lens and covering fans to managers to owners and all stops in-between.

It seems that Morris’ decision to join the board of directors at United may have been motivated, at least in part, to assist his research on The Soccer Tribe. “It had to be a balance between coming into it from the outside with a fresh perspective and then getting deep enough to understand,” he told Mike Henson of The Set Pieces. “That was made The Soccer Tribe different from other football books”.

“It would not have been enough to watch football with a fan. I had to get involved with a club at all levels and see how the institution and its people operated. I was too old to become a footballer so I became a director at Oxford in 1977. I travelled on the coach to matches alongside players. I even went on holiday with them during their end-of-season trip so that I could study them as private people as well as public players.”

I’ve selected a few pieces from the 1981 edition centred around Oxford United which show just how wide the book’s remit is and also how much things have changed, or not, since then.

Mean Streets

The Soccer Tribe devotes many chapters to cataloguing and examining the behaviour of football supporters. As most of its contents were gathered from research done in the 1970s, those who remember those times will not be surprised that crowd trouble features heavily in its analysis.

Morris draws on the work of psychologist Peter Marsh whose book, The Rules of Disorder, I have also drawn from below. Marsh notes that in 1974 at Leeds United there were a total of 273 arrests made (around 9 per game) which he works out to represent 0.02 of those attending. At Oxford United, there were a total of 83 arrests (under 4 per game) in the same time period – 5 of which were for offences involving violence, and the remainder being to do with breaches of the peace of offences under the Public Order Act. Morris misses out Marsh’s calculation that at 0.06, arrest rates at Oxford during the same period were statistically 3 times higher than at Leeds– whom Morris refers to as “a large club with a reputation for violence”.

Focussing on the effects of football violence and using the First Aid Station figures at Oxford United, in two full seasons Marsh reports that 311 people received some kind of medical treatment – an average of around 7 per game or 0.01 of the average attendance. He notes that more than half of the 311 incidents were “…simple accidents such as falling down stairs or trapping fingers in gates”. Morris adds that “this meant that an average of only three people per match were hurt as a direct result of crowd violence”. Marsh draws the following conclusion of the impact of crowd trouble: “’Out of those involving deliberate violence it was impossible to find any cases of ‘innocent bystanders’ being hurt and most of the injuries consisted of small cuts and bruises on the heads and faces of other involved Rowdies”.

To put the arrest figures in some context, in the 2023/4 season there were 23 arrests made of Leeds United fans both home and away. This is down significantly from the previous seasons where there were 69, 43% of which were at home games. For 2023/24 the Oxford Mail reported that 24 Oxford United supporters were arrested for football-related disorder – almost double the previous season’s total. This included 16 arrests for violent disorder; 6 arrests for public disorder; an arrest for entering a stadium in possession of class A drugs; and one arrest for the possession of pyrotechnics.

Analyze This

We think of Sports Science as a new phenomenon. Something which was brought into the game by scholarly Continental managers, reversing the ‘pint and a fag at half time’ traditions of days of yore. But as early as the 1920s, manager Frank Buckley was giving ‘pep pills’ (thought now to be amphetamines) to his Blackpool players to enhance their performance. When he moved to Wolves he was at the centre of the Monkey Gland scandal, where players were injected with extract of monkey testicle, which actually coincided with an upturn in results and whilst never banned by the FA, the practice died out with the advent of Planet of the Apes the Second World War.

This graph shows the results of an experiment at Oxford United in the 1972/3 season. On the Thursday before a Saturday game, players were “trained to exhaustion” and then rested until the game itself. On Friday they were fed a high-glucose diet and then kept relaxed until kick-off to avoid “prolonged adrenaline flow”. Over the 20-game experiment the results were remarkable – as you can see from the graph in the final stages of the match, goals-scored was hugely up and goals-conceded significantly down.

Morris also notes that “because of their increased stamina [the players] also suffered far fewer injuries than previously”.

We take it for granted nowadays that payers will suck on a tube of energy gel to get a boost of sugar during game downtime, but this practice of increased carbohydrate intake dates back well over 50 years to the days of Roy Burton, Graham Atkinson and Hughie Curran.

Scarf-ace

Such is the forensic detail into which he delves, Morris devotes three whole pages of the Soccer Tribe just to the wearing of scarves. He cites the work of social psychologist Peter Marsh who, in the mid-1970s, “spent three years living amongst the young tribesmen of the Oxford United Football Club”. From videos he had made of Oxford Fans he commissioned the watercolour painting below, depicting an identical ‘model fan’ in different clothing and footwear and wearing (or not) their scarf in varying positions about their person. Interesting to note that nowadays it’s rare to see the wrist or belt positioning – mostly you see scarves around people’s necks, although I wrapped mine around my head at Cardiff to ward off the chill wind and at Swansea to avoid getting sunburned.

The pictures were shown to Oxford fans who had to rate the fan-figures in terms of loyalty and ‘hardness’. By definition, ‘hard’ fans are those who willingly engage in battle with other like-minded thugs and will brave all weathers, using their scarf for tribal recognition rather than practical warmth. In contrast, ‘soft’ fans wear their scarves round their necks to keep the cold out, and shy away from any potential conflict with police or rival fans. ‘Loyal’ fans go to every game, home and away, often incurring great expense to do so, whereas ‘disloyal’ fans cherry-pick their games.

So, these definitions allow for four combinations of fans: hard/loyal; hard/disloyal; soft/loyal and soft/disloyal. Oxford fans were then asked to look the fans depicted below and determine which were which, based on attire and scarf positioning. The results were “fed into a computer” (in my mind this involved punch-cards and giant spinning reels of magnetic tape) and the conclusions drawn are both fascinating and hilarious, and speak to the times in which this research was conducted.

“Denim jackets made the models look “harder” than those without denim jackets. Club scarves, naturally, were a sign of “loyalty”. Scarves on the wrist rather than round the neck indicated exceptional loyalty and hardness. Fans wearing such combinations as scarf, flag, T-shirt, and white baggy pants struck many boys as “right hooligans”, but they did not seem as hard as most of the other models. Jeans, boots and denim jacket without a scarf pointed to hardness without loyalty, while models without scarves and who were otherwise dressed rather conventionally in casual jacket, trousers and shoes seemed both hard and loyal.”

Morris then goes on to make the distinction between the Straights and the Toughs who aren’t, disappointingly, characters from the Beano, but two types of fan neither of whom wear club colours – but for different reasons. The Straights aren’t ‘true’ fans as such as they don’t wear any colours and pick and choose their games – so are soft/disloyal. The Toughs are the ‘hard nuts’ who don’t need to display their loyalty, although they are both loyal and hard. Perhaps a modern equivalent of the Toughs are the Stone Island brigade who tend not to wear Oxford United-related gear, but can be identified by their bicep-badges and questionable haircuts. The nuances of clothing and footwear are explored further in The Soccer Tribe in the same detail that later books would analyse the Casuals culture of the 80s, It’s also worth noting that this research pre-dates the advent of replica kits, an additional variable which probably would have fried the 70s computer’s circuits.

If you’re looking for a fun game for all the family, why not have a look through the fan-pics below and work out who are the hooligans and who are the softies, and also think about what you would be if you were analysed by a mid-70s Oxford fan. Me? A loyal softy, definitely.

All in all, The Soccer Tribe is a real curate’s egg. It covers every aspect of the game from a sociological perspective, albeit sometimes seeming slightly contrived, but I can highly recommend this huge tome which is available pretty cheaply from online booksellers.