I recently read that the human brain is so complicated the human brain doesn’t have the capacity to understand it. And, if it were simple enough understand, our reduced capacity would mean we still wouldn’t be able to understand it.

To fill this perceptual debt, we’ve invented artificial intelligence, a notional idea that if something were able to consume all the knowledge in the universe, it would be able to discover things the human brain alone was unable to find. This used to be explained by the idiom of an infinite number of monkeys with infinite number of typewriters writing the complete works of Shakespeare. Now it’s known as ChatGPT. Bloody woke nonsense.

It’s not exactly early days for artificial intelligence, the idea has been around since the 1950s, but in recent years advanced technology has allowed us to navigate beyond ‘AI winters’ – periods of slow evolution – to what has become known as ‘the great averaging’.

The great averaging is the idea that current processing capability can consume vast amounts of data and produce, at best, an average response to almost anything. It’s a monkey that can write an average Shakespearian sonnet, which itself is impressive, but can’t write a great one.

Not being the possessor of a great analytical brain, I initially perceived the Leeds game in the same way as our play-off semi-final against Peterborough last season; a piece of novelty theatre, sitting in glorious isolation at the end of the day.

With no work to occupy the hours before kick-off, there was enough time to have bona fide plans for the day. The game was a treat, conveniently positioned not get in the way. We were carefree, last year was unexpected and this year we’d found ourselves six points clear of relegation. The BBC had even put a number on it, rating our prospects of going down at 2.3%. We couldn’t really lose.

But, where the Peterborough game was neat and self-contained, a densely packed ball of destiny and fate contained within 90 minutes located inside the Kassam Stadium. Friday was somewhat more complicated.

At lunchtime, the foundations began to tilt, Luton beat Derby and by half-time in the 3pm kick-offs all our relegation rivals were picking up points. By full-time Portsmouth and Stoke had both won, with Plymouth losing from a last-minute penalty. Far from the self-contained game of last year’s play-off semi-final, it was like watching football on six pitched with twelve goals, ten of which you couldn’t see, let alone defend.

I was still trying to process the fact that ‘everyone had won’ as I got to the ground. Against Peterborough, the game was all in front of us, against Leeds most of it was already behind.

There was certainly a heightened sense of occasion, the pre-match pyrotechnics were bigger and louder with one of the flamethrowers sitting in the middle of the pitch worryingly close to the highly flammable giant head of Ollie the Ox, who was wandering around nearby.

As the players emerged, the East Stand became a sea of yellow and blue. The spectacle was, well, spectacular although there was a nagging question as to whether this was for the benefit of the TV (tinpot), marketing of Oxford United football (sensible), or to inspire the players to secure the points we need to stay up (possibly unnecessary).

We started well with Alex Matos bullishly setting the tone and Cameron Brannagan drawing an early save, but the game quickly settled into its pre-destined pattern. Perhaps it was facing the might of Leeds United or simply because we’ve gradually been educated into accept what we are in the Championship, but the crowd thundered out a solid rhythm that was less of a frenzied battle cry, more like a hortator on a slave ship hammering out a steady beat on a drum for the oarsman to follow.

The aim was to defend as a unit, allowing them to keep the ball as long as it was a long way from our goal. In the main it worked, but unlike Sheffield United a couple of weeks ago, despite their lack of progress, they showed no frustration.

While we’d accepted that our role in this brooding drama was to sit and defend, shifting from defence to attack when you’re in a perpetual reverse gear was nearly impossible. It was like watching The White Lotus, it was hard to know how the static nothingness would convert into a meaningful drama.

If we did get any possession, we were so far from their goal, our only hope was to make it beyond the half-way line. The idea of making it into their box was a vague conceptual notion. The offensive aim, apart from our usual plan to win set pieces within range of the goal, was to look for Shemmy Placheta, the only player with the ability to make significant territorial gains. While they were clearly afraid of his pace, if they could avoid giving him a straight line to run into, the danger was largely averted.

Our plan was working and the fans were on board, but there seemed little prospect of us scoring. It was like sitting in a pub in the 1970s watching people buying peanuts from the display behind the bar featuring a picture of the half-naked model. The peanuts were gradually being removed, so everything was going well, but nobody was able to buy the bag that revealed the model in all her glories.

The game had a simple arithmetic, if they could keep their calm, they knew there’d eventually be enough chances to win the game. If we could keep our concentration, we might frustrate them.

After half-an-hour the breakthrough came, Jayden Bogle got down the right and centred to Manor Solomon to tap home. There were no complaints.

Thankfully, the modern game doesn’t involve much shooting, so the floodgates failed to open. Leeds fans became briefly animated at the goal, but when their team didn’t capitalise, they settled into near silence. Instead, the game drifted into an aesthetically pleasing timbre. We defended solidly; they attacked efficiently. As a result, we didn’t get opened up nor did we look likely to score. If only we weren’t a goal down.

For the final moments, Gary Rowett pushed Michal Helik up front in a moment of uninhibited lunacy, but it felt as daring as Theresa May running through a cornfield. Briefly they wobbled, slightly taken aback by 6ft 5inches of Polish muscle bashing them about. It was enough for the Leeds players to embrace each other in celebratory relief at the final whistle. This was a bit embarrassing, although, for them, the result is transient, their ambitions are greater than us.

Ultimately, this was Oxford v Leeds as produced by ChatGPT, the great averaging of two contrasting sides. They have the resources to win comfortably, which they did, we have the grit, determination and conviction to compete, which we did. It’s just our best is still worse than their average.

Ultimately, nobody really expected us to take anything from the game, and despite the results around us, the gap has only eroded by a point. If that continues, there aren’t enough games left for us to be sucked into the relegation zone. That said, a win on Monday would be nice.

While you’re here…

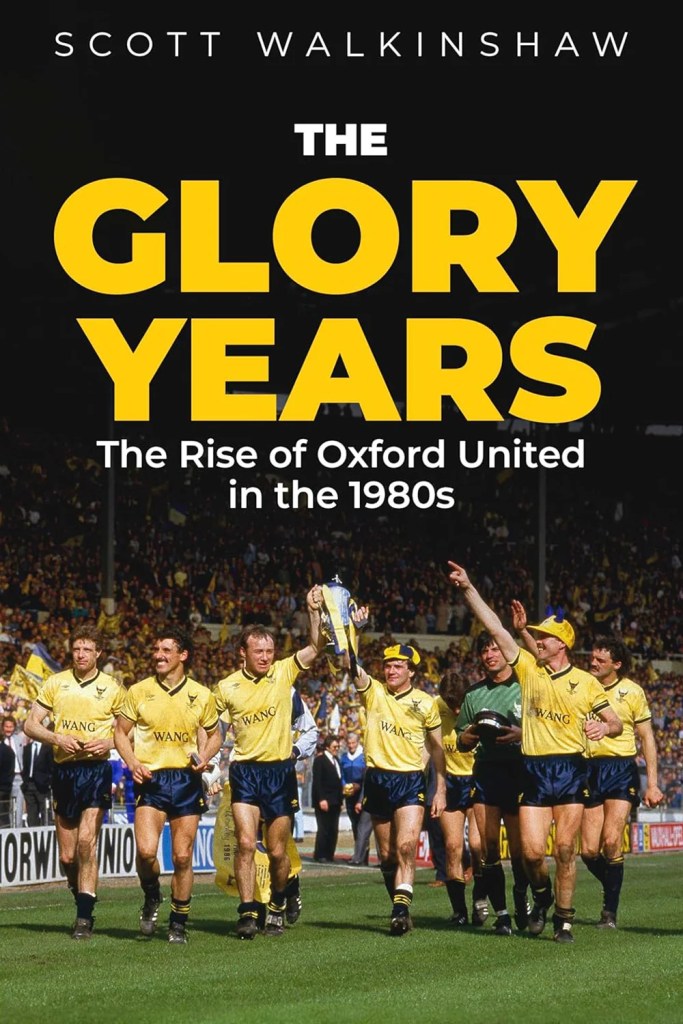

If you like this kind of thing, then you might like The Glory Years, the rise of Oxford United in the 1980s. A remarkable story of a club that survived near bankruptcy and a merger to win championships, defeat the giants of the game and win the Milk Cup at Wembley in 1986.

Leave a comment