At half-time yesterday, Peter Rhoades-Brown introduced Malcolm Shotton as guest of honour. ‘My captain’ he called him before reading out Shotton’s stellar Oxford United CV; over 330 games, two Championships and, of course, lifting the Milk Cup in 1986.

Rhoades-Brown rightly swerved Shotton’s twenty-month managerial reign in 1998/99, the last remarkable new-manager bounce we’ve seen at this level. Shotton’s impact when he joined in January 1998 was stunning, in his first fifteen games he won nine and drew two. We went from 21st in the division to 10th, briefly flirting with the idea of snatching a play-off spot. Simon Marsh and Paul Powell were selected for England’s Under 21 squad. We thought we’d found our saviour.

It turned out that Shotton’s main managerial strategy involved shouting and unleashing a tsunami of terror whenever he wasn’t satisfied. He was a terrifying disciplinarian with a near sadistic approach to team bonding. Dean Windass details his Shotton-authorised initiation with prankster Terry Gordon which involved him being threatened with a shotgun. Apparently, Gordon’s involvement ended only when Paul Tait broke his arm with a golf club in a pique of terror. Rumours of fights between Shotton and players were liege.

The mania offered only a short-term bump as financial crises, player sales and tactical limitations meant he was forced to resign in 1999.

Somehow it doesn’t feel like our turnaround under Gary Rowett, which if anything is more stunning than Shotton’s, comes from the same seething furnace that Shotton managed to stoke in his early weeks at The Manor. Yesterday’s win over Blackburn showed a level of maturity and completeness that made us look like a Championship side comfortable in its surroundings, something that was wholly absent just four weeks ago.

Clearly Rowett’s being backed in the January transfer window but with only Michel Halik making his debut and only then out of necessity, the rest of the side is the same one that Des Buckingham had at his disposal, with seven of those playing in League One last year.

So, what has Rowett done to make our stay in the Championship – dare I say it? – relatively comfortable? Has he unleashed Shotton-like volcanic motivation? Applied some subtle tactical masterstroke? Or is it just luck?

It seems to be none of these things, at least not to such an extent that it would see us transform into the form team in the division.

There’s a bloke on social media, Phil Harris, who is a music producer and DJ providing advice and training to people wanting to take it up professionally. He’s built up a substantial following by posting clips of high-profile DJs and explaining how they’re producing their mind-bending sonic collages which send dancefloors into a catatonic trance.

Modern DJ equipment is unrecognisable from the old set up of two turntables and a mixer. Controllers are used to access software with the power of a traditional music studio meaning you can do pretty much whatever you want with the sound. Harris reveals, rather than feats of timing and dexterity, most of the tricks involve pressing the right buttons on the DJ controller in the right order, meaning modern DJ-ing is about 80% waving your arms around.

Perhaps this is Rowett’s power play, as an experienced manager in the Championship he has a deeper appreciation of the full range of capabilities at his disposal and is more confident about giving the players their full responsibilities, just allowing them to play.

Maybe Des Buckingham didn’t appreciate the resources he had to compete in the Championship. Who’d have blamed him? Nobody expected promotion, fewer still expected us to be competitive at this level. Buckingham often looked like he was navigating games playing five-dimensional chess inside his head trying to outfox his opponents. It worked surprisingly well, but equally, maybe he didn’t need to overthink and internalise the challenge so much as all the capability he needed already existed on the pitch.

Let’s face it, it’s a shame that TikTok is being banned in America because someone could build up quite a following just revealing how to access the secret functions in Will Vaulks. Over the last couple of games he shown long range shooting, a howitzer throw-in, back flips, raking cross-field passes. None of these seemed possible a few weeks ago.

While the side transforms in front of our eyes it sometimes feels like things are moving too quickly. So, it was reassuring that the difference between the sides ultimately came down to the one thing that never changes.

With twenty-three minutes to go, Cameron Brannagan stood over the ball. Vaulks and Shemmy Płacheta were either side whispering in his ear. I’m never really sure how planned these things are, you would think that these days wherever the ball is placed for a free-kick, the person taking it has been decided days ago on the training pitch. It never seems like that, players always seem to compete to be the one to get the ball, like kids bickering in a playground.

But if there was a debate, Brannagan wasn’t engaging. While everything changes around him, he’s had to resist becoming engulfed by it all. He’s had be part of a side that had a dalliance with relegation to League Two, won at Wembley and is now competing in the Championship. It would be easy to become intimidated by the changes happening around him, paranoid that he might be the next to go, but every time we’ve taken a step forward, we find that Brannagan has done it first.

He stared at his feet. All the things that mattered were fixed – the size of the target, the geometry of the ball – these things don’t change. Brannagan even has the reference points of his surroundings; the relative distance between an exit sign in the East stand and the frame of the goal or the dimness or otherwise of the floodlights. He’d been there so many times, sometimes in front of a near-empty home end or now in front of one that’s full voiced.

His strike was simple, straight and true, it had a purity about it. The keeper gave up long before it reached his orbit, he could only hope that somewhere there’d been a miscalculation or a variance. There hadn’t, the ball rifled into the top right-hand corner and, as is familiar, Brannagan raced towards the East Stand, sliding on his knees before a bundle of players land on top of him. He’s probably had forty or fifty different players doing that to him over the years.

Afterwards, Jerome Sale declared Brannagan an honorary Oxonian for his use of the phrase ‘big old boy’ to describe Michel Helik. It’s true, he should be free to drive his sheep across Port Meadow for what he has done for this football club. For all the change and success we’re enjoying now, it is all the sweeter for the fact he’s still part of it.

While you’re here…

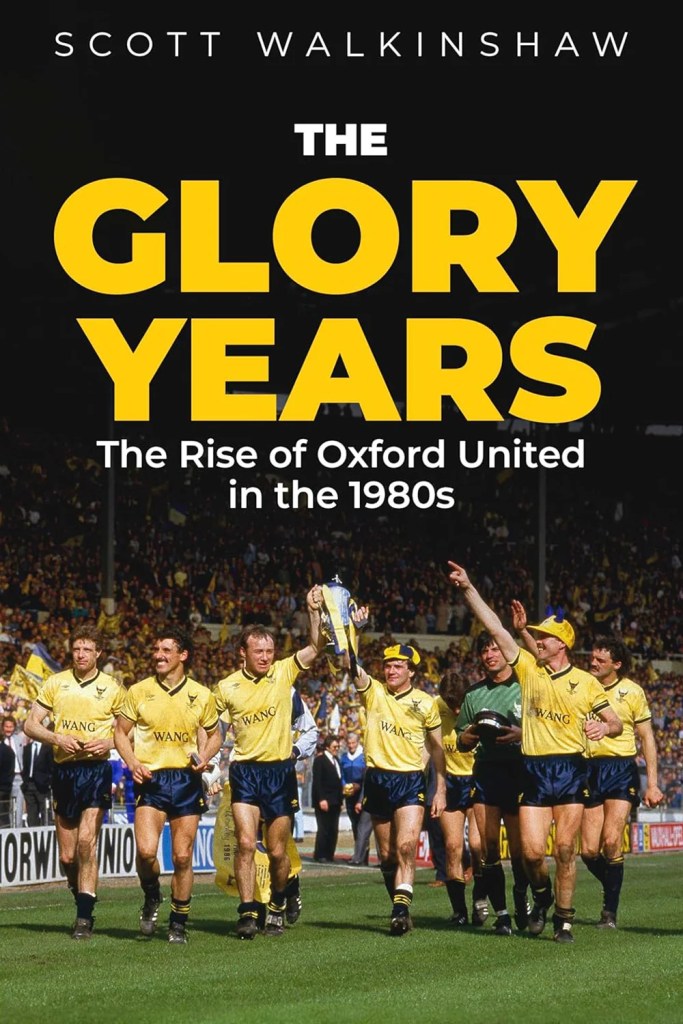

If you want to read about Malcolm Shotton’s spectacular reign as Oxford captain, The Glory Years is published on the 27th January and now available for pre-sale here. It is the remarkable story of Oxford United’s rise through the divisions from near bankruptcy to winning at Wembley.

Leave a comment